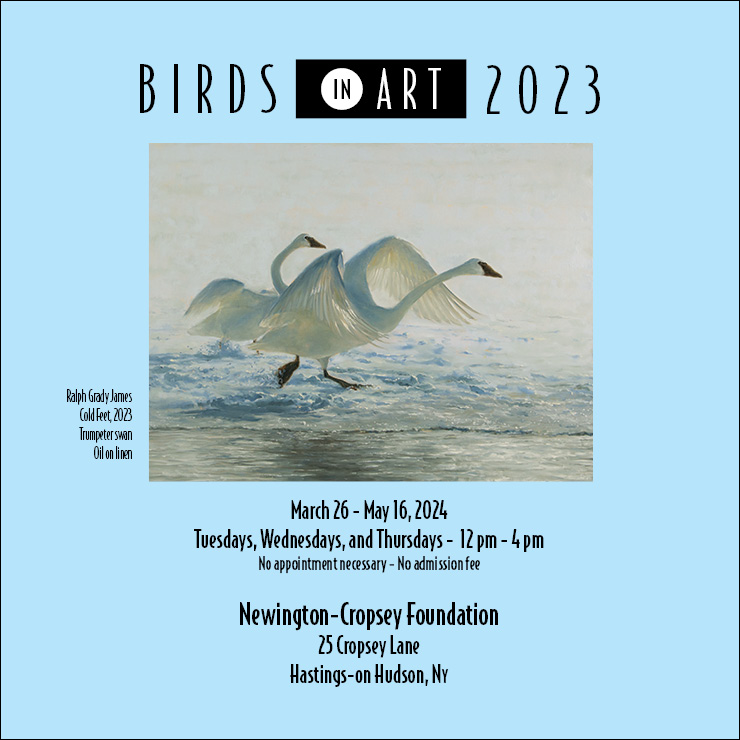

Instructions to Follow Upon Your Return Home:

Assuming my mother would not have a random list of post-birth instructions lying around from somebody else’s childbirth, I thought this might be hers from the dawn of me or my brother (1973, 1969). But various clues in this told me otherwise: my mom likely wouldn’t have had a Hartford-based doctor since we lived in Bristol, CT. This Dr. Frank O. Wood wasn’t the name I heard growing up as the doctor who had to interrupt his dinner to launch me, whose name I can’t recall but it’s not Wood. And that six-digit phone number.

According to a thread in Reddit, such a short phone number—before the national standardization required by subscriber long distance calling was established—might have been in play until the 1960s in a populated place like Hartford. My mom completed the final piece of this minor mystery by confirming, from checking in her own baby scrapbook her mother had compiled, that there is the office of Dr. Howe and Dr. Wood listed in the details of her own birth. My mother was born at Hartford Hospital, Thanksgiving Day, 1942.

So, time period established and in the 1940s apparently “permanent waves” are essential enough an element in women’s everyday lives to actually merit listing on the list of physician-approved activities after childbirth “as soon as you feel like it.” Also, no problem douching with vinegar in a few weeks but zero mention of any of the breastfeeding that might alleviate the mysterious issues of that breast pain and discharge!

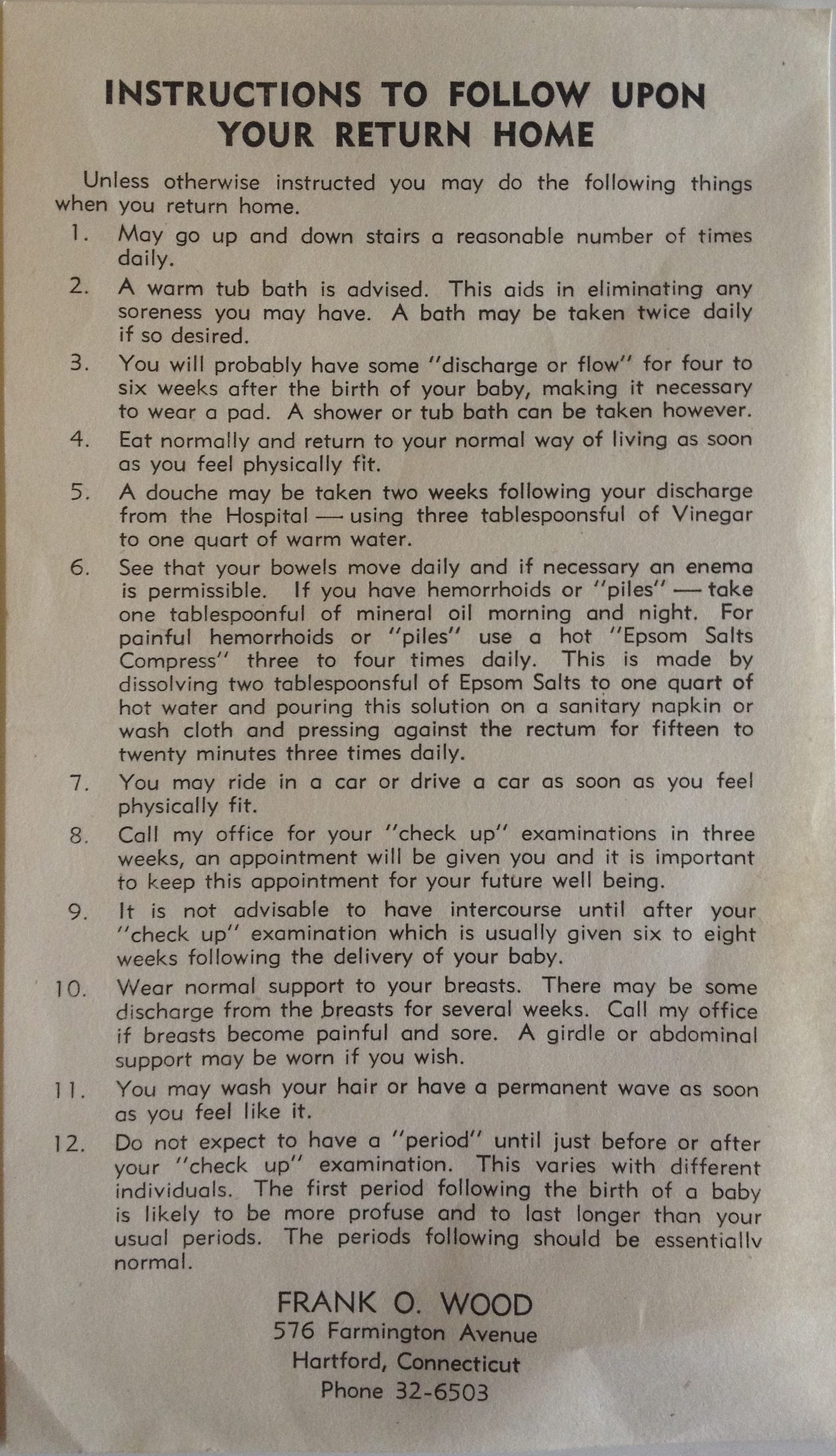

A first-head account comes from the beauty shop in Wisconsinhistory.org:

“It took all day, and cost $1 each….First our hair was washed and cut, then we waited and waited. There were women everywhere in different stages of getting beautified. Everyone was waiting….My hair wound up on spiral rods so tight that I thought I would never blink again [and] after the machine that looked like a milking machine was attached to the rods, I couldn’t move. [Then] it began to steam and tears rolled down my checks. …[finally] someone got a blower and cooled my head here and there, but my scalp was scalded.

In the end, Kanan described her hair as a blonde “haystack.” Because of frequent mishaps like this, some hairstylists referred to permanent waves as “pocket perms,” a term that poked fun of the fact that the drastic chemical and temperature measures of their equipment often caused a client’s hair to break off during the process. In the hopes that a client would be none the wiser, the stylist would sometimes hide the broken tresses in her pocket.”

Or go home and make a cheap DIY mishap in three hours, up to you!

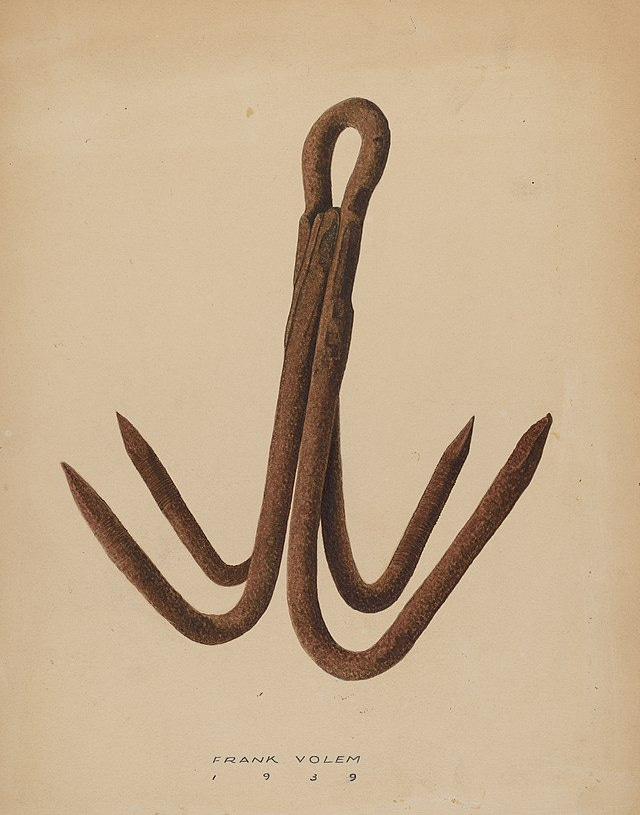

On Oct. 26, 1934, three black Hartford women set off on a fishing trip along the Connecticut River into Keeney Cove in Glastonbury. The trio had been fishing for pickerel from around 10 am until almost 3 pm in a boat they rented. They complained it was leaky from the outset and spent all day bailing out to keep afloat. As they finally made their way to shore, the boat filled up more rapidly and capsized, sucking the women into the strong current. One woman, Ada Wheeler, 39, managed to get her footing and climb ashore to safety, calling to nearby road crew workers for help.

“Dickau dove into the cold water, swam to Mrs. Bennett’s body and towed it ashore. The body had not sunk.

Meanwhile members of the Glastonbury Fire Department arrived with grappling irons. The body of Mrs. Hill was located after about 15 minutes of grappling. A lungmotor was used on the women by John Naylor of South Glastonbury but they could not be revived. Dr. Frank O. Wood of Glastonbury visited the scene of the drowning soon after the accident and said that the women were dead.

Dr. Lee J. Whittles, Glastonbury medical examiner, could not be located Thursday afternoon and the bodies stayed at the cove several hours before Dr. H.J. Onderdonk of East Hartford arrived and permitted them to be removed. They were taken to the L.B. Barnes Funeral Home in Hartford.

Keeney Cove has been a favorite fishing place for large groups of Hartford Negroes this summer, despite the dangerous currents. The cove waters “bottle-neck” at the Keeney Cove Bridge and the current there is swift. It has been the scene of a number of drownings in recent years. At this season pickerel are the principal catch.”

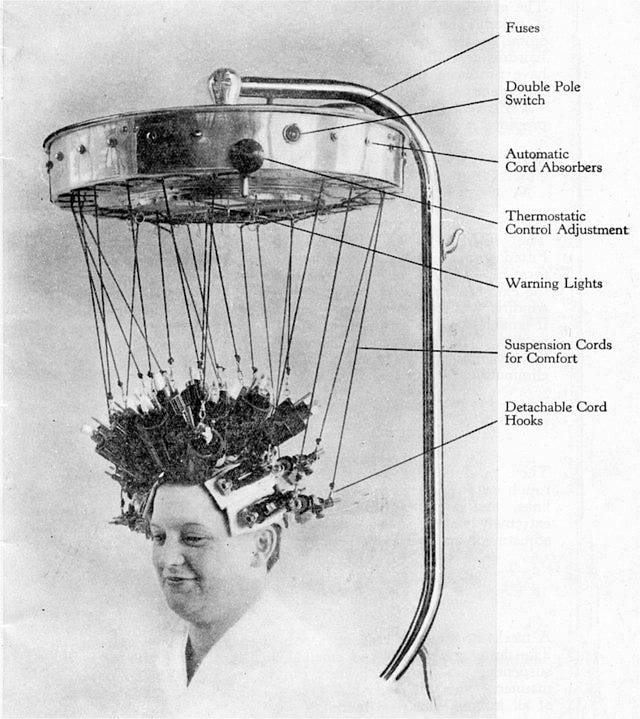

The “grappling irons” used to fish out the women might have resembled this item from 1939:

The “lungmotor” used to attempt to revive the women is described by the Woodlibrarymuseum.org:

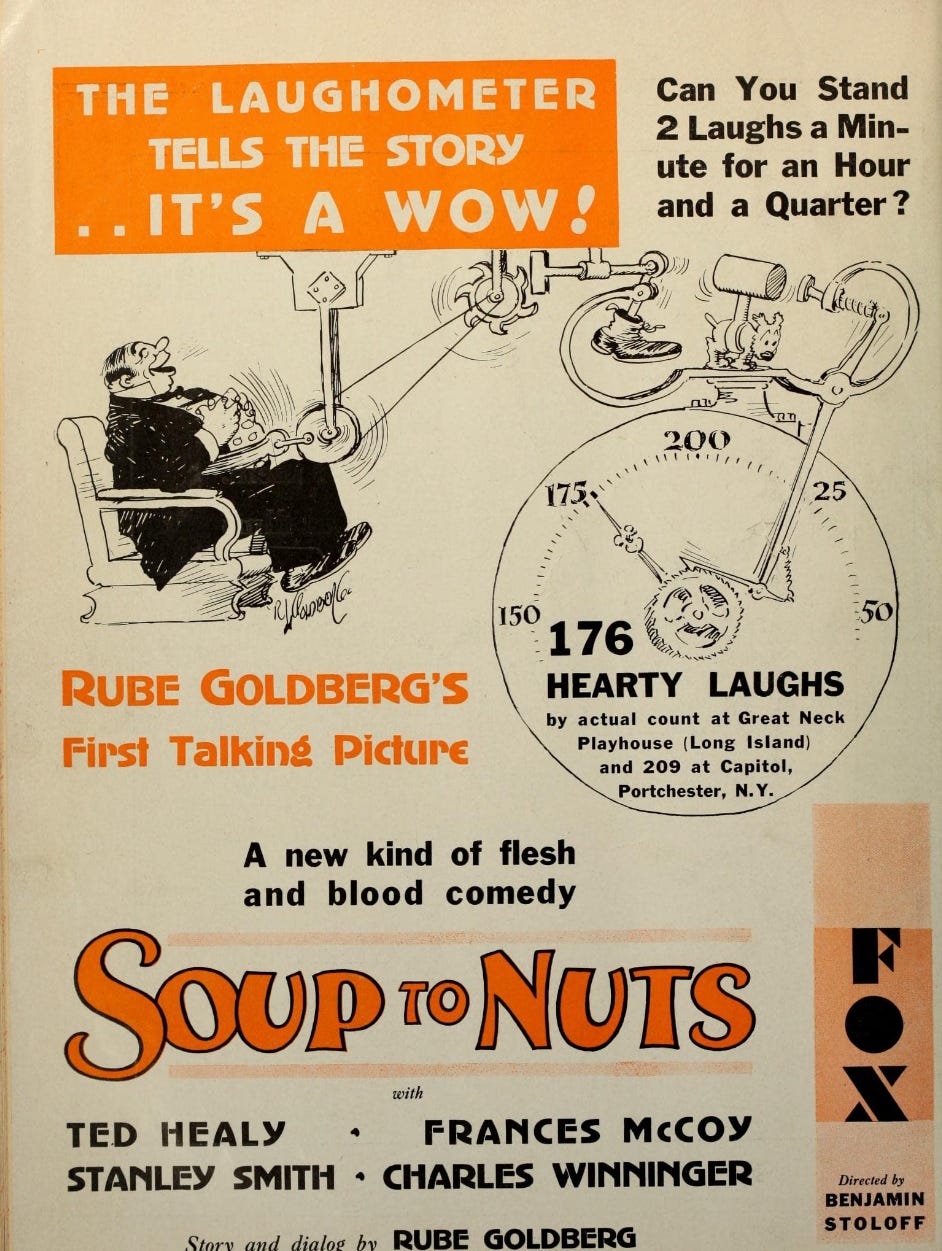

These were heavily advertised from 1913 into the 1920s, and were purchased by numerous public works and fire departments, hospitals and mining companies. Unlike the Pulmotor, the Lungmotor was hand-operated. Pushing the handle down forced air, oxygen, or a combination of the two, into the victim’s lungs. Raising the handle suctioned the air out again. Although the apparatus could be adjusted to limit the pressure applied, investigators judged it to be safe only in the hands of experts. But the first responders who used it were rarely experts. In the 1930 movie, Soup To Nuts, the comedy trio later known as The Three Stooges exemplify the wrong way to use a Lungmotor.

I can’t find a clip of this movie with a lungmotor in it, but here’s a poster. Soup to Nuts was written by none other than the cartoonist synonymous with complicated machines, Rube Goldberg.

And in the midst of this anything-but-comedic chaos at Keeney Cove was Dr. Wood (man who eight years later would potentially deliver my mother) declaring these women dead, but not officially apparently, as the bodies still had wait for a licensed medical examiner for hours. Did these women have children at home they intended to feed fish that night? I have so many questions, never mind what extra tortures they might have had to go through to get their hair done.

While it’s possible to track down plenty of info on permanent waves, terrifying claws, and wonky breathing support devices, the only evidence I can find that these two black women, Josie Bennett, 42, and Pearl Hall, 22, existed was from the day that they drowned.

Krista Madsen is the author behind wordsmithery shop, Sleepy Hollow, inK., and producer of the Home|body newsletter, which she is sharing regularly with The Hudson Independent readership. You can subscribe for free to see all her posts and receive them directly in your email inbox.

Krista Madsen is the author behind wordsmithery shop, Sleepy Hollow, inK., and producer of the Home|body newsletter, which she is sharing regularly with The Hudson Independent readership. You can subscribe for free to see all her posts and receive them directly in your email inbox.

Print

Print